Lifespan of a Honey Bee (Worker, Queen & Drone)

We all know they're amazing workers, but what does life look like for a honeybee? Find out more about nuances in bee longevity and how this contributes to the hive in this article.

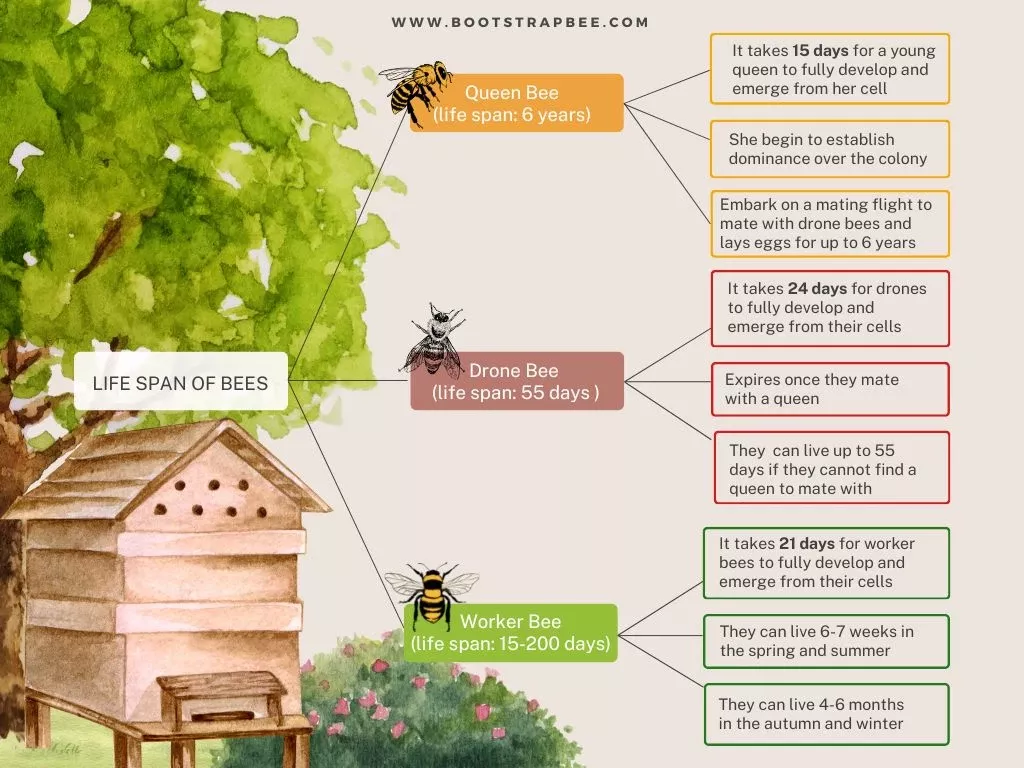

A worker bee will live six to seven weeks in the spring and summer, and four to six months in the autumn and winter. Male drones will live for 55 days, and queen bees outlive both by six years.

What could be the reason behind the similarity in lifespan between drones and workers, even when drones only have one job and workers have so much to do? And why do queen bees outlive their peers by a mile? I'll walk through the answers to these questions and more in the article below.

Summary

- At most, worker bees will live seven weeks in the foraging seasons and six months in hibernation. Drones will live for 55 days before they are kicked out of the hive. Queen bees will live for six years, max.

- Workers literally die of hustle culture, drones die after mating, and queens die when the new queen stings them to death in a process known as supersedure.

- Aside from a natural death, honey bees may also pass away from disease, predators, invading honey bees from another hive, and chemical poisoning

On this page:

Why Do Bees Have a Short Lifespan?

Honey bees, especially the workers, take on a variety of jobs and do a lot of heavy labor during the spring and summer. They literally live to work and this is what affects her lifespan: the average worker bee will move from one job to another as they grow older, and each job grows more dangerous the farther they go.

Workers start off nursing, cleaning, and building comb. When they're older, they start undertaking and guarding. Finally, they grow into the role of forager bee, which is the most dangerous duty and the most physically taxing on their body as well.

Bee flight is particularly arduous, and at least until the early 2000s, a physics mystery. As relatively larger insects, bees would be expected to flap their wings slower and cover the same wide arc as other flying bugs. Instead, they flap furiously at 230 beats per second and only beat their wings over a short 90-degree arc. This quickly leads to the wear and tear of such an important part of their bodies, but true to their work ethic, they will continue foraging until they pass on.

What Is the Maximum Lifespan of a Bee?

A honeybees' maximum lifespan will depend on whether they are a worker, a drone, or the queen bee. Female workers only live six to seven weeks in the spring and summer, and six months in the autumn and winter. Male drones will live for 55 days, and queen bees outlast both by lasting six years.

Lifespan of a Male (Drone) Bee

Drones will emerge 24 days after the egg is laid, in contrast to workers who emerge after only 21 days. They live short lives that are dedicate to mating with a queen. Unfortunately, the mating process kills the drone; the male bee's sex organ is torn off after a few seconds of mating because it is barbed, much like the stinger on female worker bees.

If a drone does not find a queen to mate with, they may live for about 55 days before their siblings kick them out of the hive. Once they've been shown the door, they die from exposure, starvation, sickness, and predators.

Lifespan of a Queen Bee

The royal treatment

When a colony starts sensing the need for a new queen, the workers will start raising new queen bees. Nurses will pick 10 to 20 newly hatched female larvae and start feeding them royal jelly. This is a milky white substances the bees secrete from the top of their heads. This special diet transforms the female larva's reproductive system and is what's responsible for making her a queen.

When queen bee larva is ready to metamorphose, the workers will cap the cell. After 15 days, she will chew her way out with the help of a few workers.

Eliminating the competition

Queen bees don't play around. The minute she's done chewing her way out of the queen cell, she sets out to kill her own sisters, who are the other new queens raised by the nursing bees. She "pipes" out to them repeatedly, which is a high-pitch chirp used to locate the rest of the queens and initiate a fight to the death. Even the queens who are still in their cells will pipe back. In their case, the queen will sting them to death before they've even had the chance to hatch.

Embarking on a mating flight

After the queen bee has established herself as the only queen in the colony, she will embark on a mating flight from the hive and mate with male drone bees. This flight will give her the reproductive capacity to lay fertilized eggs for the next three to five years.

Settling in the hive

Once she is finished mating with the drones, the queen will make her way back to the hive. If the old queen bee is still alive, then the new queen will kill her and take over laying eggs. She will now live the rest of her life attended by the workers.

Most of a queen bee's days will involve walking around the hive, dragging her abdomen wherever she goes. She makes regular inspections into the bottom of all the honeycomb cells in the brood chamber and if she finds an empty cell, she'll drop her abdomen in to lay an egg. On a good summer day, queen bees are capable of laying up to 2,000 eggs.

From time to time, her attendants will groom and feed her while she stops to take a break. These attendants are found surrounding her and aside from helping her, they also spread her queen pheromone through the hive. This tells the rest of the bees in the hive that the queen is healthy and hard at work, like them.

Superseded by a new queen bee

Over time, the queen will not be able to lay as many fertilized eggs and the amount of queen pheromone she excretes will wane as well. At this point, the worker bees in the hive will start raising new queens. When a new queen has hatched and is ready to take over, she will find the old queen (assuming the old queen has not passed away yet) and sting her to death.

Why does the queen bee live so long?

Normally, animals need to make a choice between living long and being capable of mass reproduction. This means that the more energy and nutrient that is invested in laying eggs or giving birth, the faster the animal will age and the shorter its life expectancy.

However, the queen bee has found a way to get the best of both worlds. Despite laying over 2,000 eggs a day, they are expected to live ten times as long as the worker bees in the hive. The same goes for termites, ants, wasps, and other bees. Research into this phenomenon is still ongoing, with one study concluding that in hives where the queen bee was removed, worker bees who reactivated their ovaries were more resilient against a virus that can cause lethal infections.

Bee Lifespan per Season

Worker bees can live for two to six weeks in the summer and roughly 20 weeks in the winter. The difference in lifespan can be attributed to the amount of hard work they have to do. After all, this is when the workers are most active and will take on the most number of jobs. Literally working themselves to death is a common occurrence.

Once winter sets in, the queen bee stops laying eggs. As a result, the brood pheromone that signals workers to start their first job as nurse bees is not released inside the hive. This means that the honey bees never officially enter "job mode." They have a different biology from honey bees and even a different name—diutinus bees. Ultimately, the lack of brood pheromone is what helps them live longer and survive the winter.

When the queen bee starts laying eggs in the spring, the diutinus bees are exposed to the brood pheromone. This will prompt them to begin working and become nurse bees or foragers.

Meanwhile, male drones are only alive in the summer to mate with the queen. Any remaining drones will be kicked out of the hive before winter sets in.

How Long Do Bees Live in the UK?

The United Kingdom only has one species of honey bee, the European honey bee. This is one of the most common honey bee species. Female workers have a life expectancy of 30 to 60 days, while male drones live for 21 to 32 days.

What Could Shorten a Bee's Lifespan?

There are plenty of threats to a bee's life. They could be killed by bees from another colony, eaten by animals, or even dead because of overwork. However, the two most alarming causes of death are the bees' susceptibility to disease and infection, and the modern-day use of pesticides in the field.

Pollen consumption, the amount of protein consumed, and their levels of activity are also factors that affect a bee's overall lifespan.

A new study conducted by entomologists from the University of Maryland found that individual honey bees who were kept in a controlled laboratory environment lived 50 percent shorter lives than the ones in the 1970s. While colony turnover is a natural occurrence, beekeepers in the US have reported higher loss rates in the past ten years. Aside from struggling to deal with the loss of life, it also meant that they had to shell out more for replacing these colonies and keeping their operations viable. Ethical beekeeping will be vital to making sure that honey bees continue to thrive on earth.